PERGERAKAN Tenaga Akademik Malaysia (Gerak) notes with interest the

December 13 statement by the Public Universities Vice-Chancellors and Rectors

Committee (JKNC/R) taking issue with criticisms of public universities’

obsession with international university rankings. JKNC/R’s piece, while

directed at Gerak, is clearly prompted by our member Lee Hwok Aun’s

article.

We welcome the JKNC/R’s response, and the attempt to assure the

Malaysian public that public universities are not obsessed with the

rankings.

We wish we could be confident about these assurances. Unfortunately, the

JKNC/R’s commentary leaves more questions than answers. In particular, four

issues are still hanging.

First, does this article represent a consensus among vice-chancellors

and rectors? We also note the opinion of International Islamic University of

Malaysia rector Professor Dzulkifli Abdul Razak, who wrote in his NST column

that he is “increasingly unsure of the worth of the ranking game”, and that he

is “of the opinion that the whole exercise is ‘intellectually dishonest’,

perhaps bordering on unethical”.

Do other vice-chancellors or rectors harbour such deep

reservations?

Gerak is also concerned in this regard about the lack of disclosure on

the pursuit of rankings more generally, including the question of

funding.

Public universities operate using public funds. Any expenditure must be

beneficial and bring positive returns to society at large. Do the benefits

gained from the pursuit of ranking outweigh the amount of money spent on

it?

Unfortunately, little information has been provided by all public

universities about the costs involved in pursuing the rankings game.

For instance, how much has been spent on hosting foreign faculty and

students (for internationalisation marks)? How much has been spent on page

charges (for publishing in paid publications, increasing number of papers and

citation numbers)?

How much money has been put aside by universities to house special units

and personnel to satisfy the ranking pursuit? And so forth.

It would have been great if the JKNC/R had shed some light on this

as well.

Second, the JKNC/R speaks soothing words about the benefits and limits

of rankings, but neglects to respond to the specific issues raised by

Lee.

Everyone, even QS, will admit that the rankings have limitations and

flaws. The JKNC/R article evades the specific issues highlighted in Lee’s

article, instead choosing to dwell on generalities that are easily agreeable

but not meaningful for addressing the problems at hand.

They merely note, “while recognising that university rankings are here

to stay, we are aware of their many limitations, their intended and unintended

biases, and their convenience-based usage by institutions and other parties.

They cannot be the one and only measure of excellence”.

It is worth recapping Lee’s arguments, which should spur our university

administrations to reconsider the dominant role of the rankings criteria.

The recent experience of Universiti Malaya (UM), as Malaysia’s top

ranked university that other public universities will likely model, is highly

pertinent.

Is the word obsession causing discomfort? Call it obsession, fixation,

or preoccupation, but the underlying issue is the same. UM is used as the

dominant yardstick despite a host of problems and deficiencies.

UM’s soaring performance in the overall rankings masks backsliding on

various fronts.

All of UM’s flagship programmes, which breached the top 50 in subject

rankings and were lavishly celebrated until 2017, have fallen down those lists

since then.

UM’s score on the QS system has improved the most in citations – which

has biased the universities’ resources and reward systems toward highly cited

research – and in “reputation” as reported in voluntary surveys (not randomly

sampled). On the internationalisation of staff and students, which are based

more objectively on empirical data, UM’s score has continuously declined.

Whether UM is obsessed, preoccupied or fixated with the rankings is a

question of attitude. To gain some insight, let’s consider the administration’s

media statements, which reflect the issues and measures of success that it

chooses to tell the world.

From 2017 to 2019, 11 out of 18 media statements celebrate UM’s

rankings. None of the others concern academic achievement; six are

administrative or non-academic in content.

Other universities do not publicise such all-consuming enthusiasm for

their ranking scores, but you do not shout so loud when your rank is above 300

or 200. Will they become more consumed if they start to breach the top 200,

then possibly the top 150 and 100? It feels like they will follow UM.

Thirdly, the JKNC/R suggests the teaching and internationalisation of

universities as major priorities that are enhanced by participating in the

rankings game, but overlooks how rankings either have little to do with the

teaching dimension, or have a dubious record of delivering benefits.

JKNC/R says the “main purpose is to support students’ pursuit of their

academic goals”, but teaching factors in negligibly in the QS rankings. If

JKNC/R is truly holds this view, should they not decisively declare rankings as

a secondary priority?

They go further in specifying some benefits of the rankings, notably

that it enhances reputation and provides a reference for prospective

students.

This is the biggest element of QS’ business. But is it delivering? The

JKNC/R statement did not specify Malaysian or international students. Let us

consider both in turn.

For the JKNC/R to expect Malaysian university applicants to refer to the

rankings is dumbing down the process.

If it is true that applicants actually use the rankings as a primary

reference, this is a major indictment of our education system which needs to be

redressed.

Malaysia has only 20 public universities, and many universities specialise

in particular programmes. It is hard to imagine the international rankings

adding anything meaningful to the applications process.

UM, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

(UKM), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) and Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM)

attract the cream of the crop because they are more established and

prestigious, and information and alumni testament are abundantly available to

make informed choices.

In addition, what sort of students do we desire? If they really do rely

on the rankings rather than their own in-depth research to find a good

programme that matches their interests and abilities, this should actually

cause alarm because the system is stifling their brains.

We should instead invest in educating and counselling them on how to

research and select their choice programmes, perusing university websites and

lecturer profiles, and so on.

Let’s look at international students. Rising up the rankings generates

publicity and can enhance universities’ brand. But the recent track record is

woefully lacklustre.

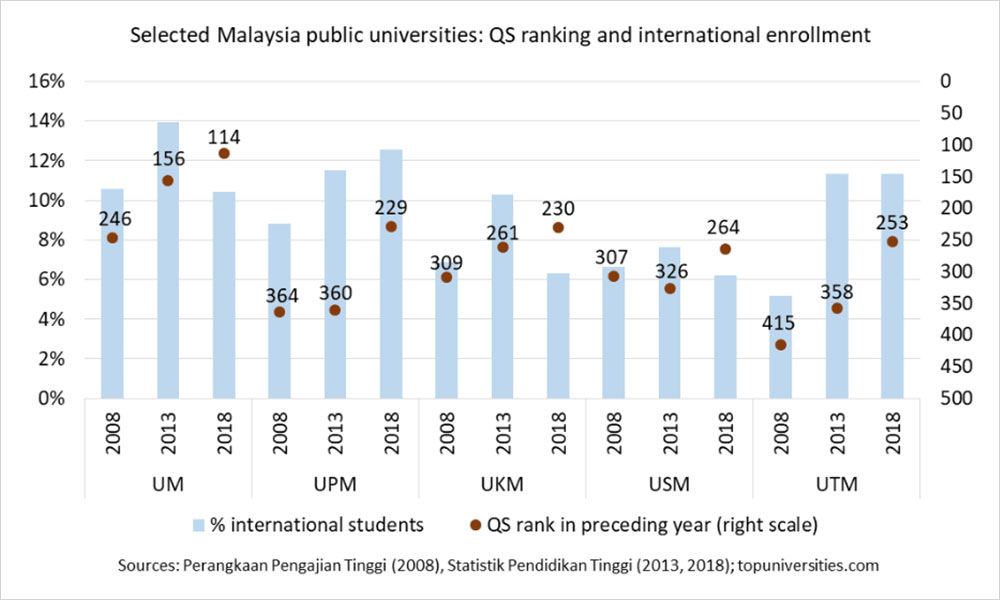

The chart below shows international students share of enrolment and the

QS ranking of five established universities of the preceding year, which would

be referenced by prospective applicants.

Between 2013 and 2018, UM, UKM and USM steadily improved their rankings,

and internationalisation fell. UPM and UTM steeply climbed the QS ladder, but

international student shares only inched up marginally.

The JKNC/R, in extolling the internationalisation benefits of rankings,

presumably includes research collaboration in the mix. This is even more

serious than the issue of students referring to rankings in their decision-making.

Any experienced scholar will know that expertise and academic records,

personal ties and networking, are the decisive bases for international

collaboration and productive endeavours. Institutional rankings, if factoring

in at all, are an afterthought.

We hope our university administrations focus on academic staff

empowerment rather than relying on the rankings to boost internationalisation

of research.

The fourth and final problem with the JKNC/R statement is simple and

fundamental. We read the closing paragraph, which reveals that this committee

of university leaders is waiting for the Education Ministry to decide whether

the rankings matter.

The reluctance of vice-chancellors to exercise their intellectual

faculties and professional autonomy, and to declare their own stance, is

astonishing. The JKNC/R justifies the policy of prioritising rankings without

critically addressing the limitations and flaws, and ultimately deems the

practice and the current key performance indicators template will continue

because the ministry says so.

Indeed, many systemic and deep-seated problems persist, but all the more

Gerak calls for vice-chancellors and rectors to rise up to the leadership and

rigour expected of their rank.

GERAK

Executive Committee

22

December 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please provide your name and affiliation